call to action

We ask that Cornell restore right relationship with earth and one another on Gayogohó:nǫˀ Lands.

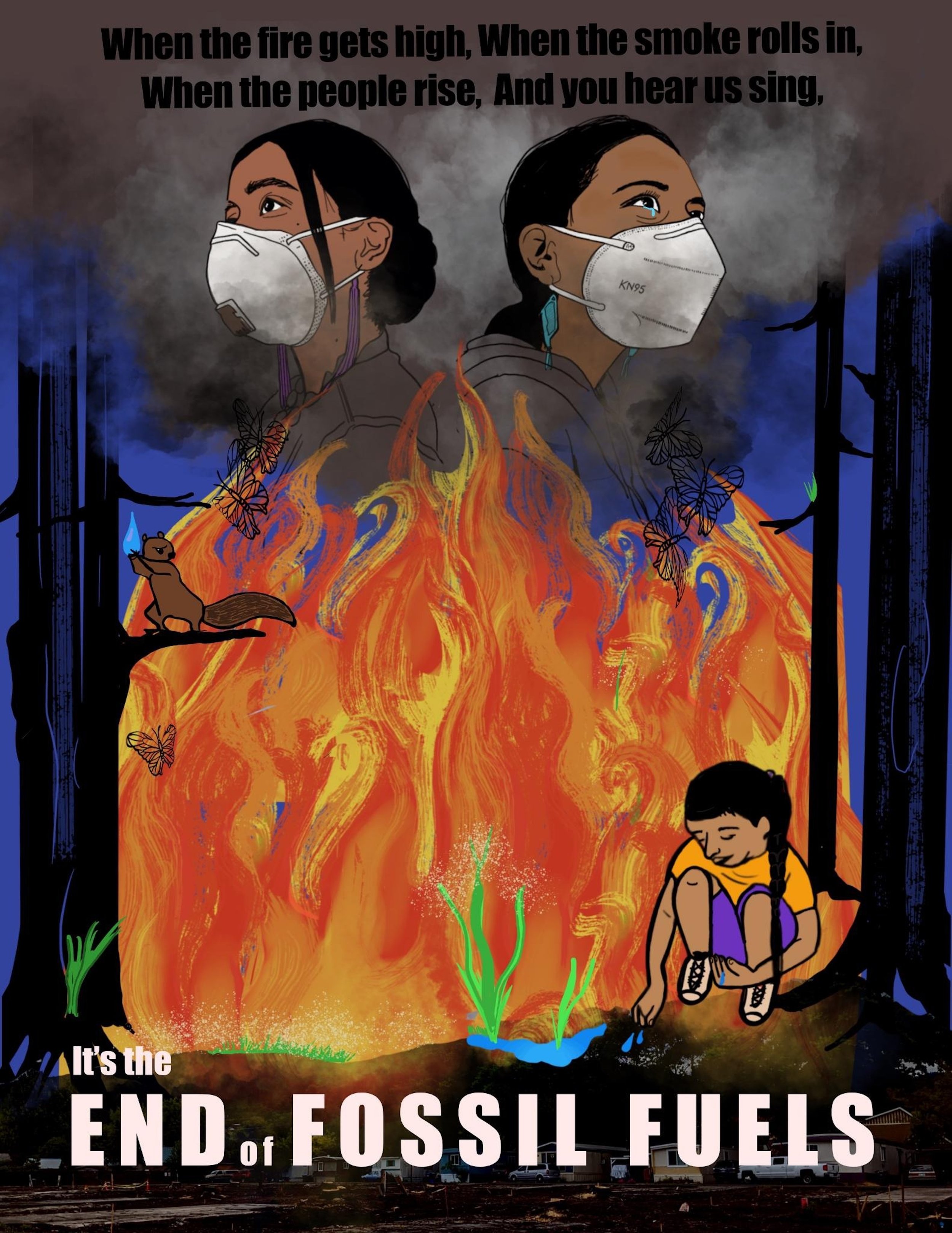

Our Call to Action takes inspiration from the Indigenous principles of the Honorable Harvest to transform Cornell’s response to the climate emergency.

What would it take to restore right relationship at Cornell?

Cornell on Fire draws its principles from climate science, Indigenous knowledge, and our own local experience. At the heart of our movement is a commitment to the question: How can the Cornell community restore right relationship with earth and one another upon Gayogo̱hó:nǫɁ lands? “Right relationship” is a concept that comes to us from Indigenous frameworks. Living in right relationship involves reciprocity: never taking more than what you need and giving back to what you take (Michael Kotutwa Johnson, 253rd-generation Hopi agriculturalist). It entails living in balance with the rest of the living world (Cornell Professor Michael Charles, Diné [Navajo] Scholar). It requires us “to live as if your children’s future matters, to take care of the land as if our lives and the lives of all our relatives depend on it. Because they do.” (Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass, pp. 214-15).

A year ago, we had the opportunity to ask renowned Indigenous plant scientist and ecologist Robin Wall Kimmerer how Cornell University could restore right relationship. Her response: refer to the principles of the Honorable Harvest. This Call to Action outlines how our movement interprets those principles in the context of university climate action, while Our Demands seek to apply these principles across all university sectors.

As activists who are positioned in the mainstream, we are challenging ourselves to go beyond our usual institutionalized frames of reference to weave together climate science and Indigenous knowledge systems for unconditional accountability. We take heart from Dr. Kimmerer’s observation in Braiding Sweetgrass that “the canon of the Honorable Harvest is poised to make its comeback, as people remember that what’s good for the land is also good for the people” (p. 195). We hope that by framing our work in light of these time-tested principles, we can contribute to the forms of climate activism and education that are most needed.

Below, our Call to Action invites you to envision how the Cornell community could carry out its mission and operations on Gayogohó:no lands, honorably.

Scroll down to explore with us what an Honorable Harvest in higher education might (or might not) look like.

We know that the systems that support life on earth are approaching catastrophic tipping points. Earth’s biodiversity is vanishing, the climate is changing faster than anticipated, the impacts are worse than predicted, and we are gravely unprepared. The totemic goal of keeping the world below 1.5C warming above pre-industrial levels is vanishing, and with it, our chances of averting irreversible damage to livable habitats. Climate breakdown has begun and the majority of IPCC scientists believe they will see catastrophic changes in their lifetimes. Many communities are seeing catastrophic changes right now.

Yet institutions behave as if they do not know our life support systems are failing. Globally, today’s carbon-cutting policies are so inadequate that they put us on track for 3°C (or more) of heating by 2100, what some leading scientists describe as a “catastrophic climate endgame.” Locally, Cornell pursues business as usual, making “sustainability” changes at the margins, indulging in traditional academic pursuits and carbon-intensive operations.

We must take care of the ones who take care of us: we need social tipping points for climate mobilization.

Climate change awareness and the imperative for justice are pushing more and more people to the tipping point between indifference and action. Around the world, 4 in 5 people support doing “whatever it takes” to limit climate change. Here in Ithaca, the local landscape is charged with active campaigns for climate justice. In fact, Cornell itself proclaims that it is “uniquely positioned to operate at the speed, scale, and scope required to confront climate change.”

If institutions like Cornell are poised to leap from incrementalism into transformative action, we also know they will not do so in the absence of significant pressure. Energy insiders at Cornell tell us: Cornell will only meet its climate goals if students and faculty hold them accountable. Indeed, it was only due to student activism that the current Climate Action Plan was formed, which was a preliminary step in the right direction. But at that time (2001), students warned that realizing the plan would hinge on continued activism by the campus community.

If you work for Cornell, learn at Cornell, teach at Cornell, or live near Cornell, please realize: Cornell will not meet its climate goals unless you hold them accountable. We can create social mobilization tipping points in response to climate tipping points. Local climate activism is far more powerful than most people realize. Empirical evidence shows us that individual and collective action is most powerful when it focuses on the “institutions you can touch”– and Cornell is an institution in need of being touched.

“The fact is, we have enough voices. Now we just have to start singing together in a chorus that’s loud enough for the world to hear.” (Cornell Professor Caroline Levine, in her call to action to colleagues.)

In 2019, 11,000 scientists issued a declaration of climate emergency, stating that “the climate crisis is closely linked to excessive consumption of the wealthy lifestyle.” The International Energy Agency explains that “substantial and rapid action by the richest 10% is essential to decarbonise fast enough to keep 1.5°C warming in sight.”

Joining Cornell means joining the carbon-intensive lifestyle of the globe’s “polluter elite,” who use more carbon than the bottom 66% of humanity combined. They are taking more than half. Even if the rest of humanity cut their emissions to zero now, the globe’s top 10% would blow through our global carbon budget by 2033. They are leaving none for others.

This radical carbon inequality underscores why the climate emergency is a climate justice emergency, with responsibility and consequences distributed very unequally. In a human rights violation on an inconceivable scale, the majority of humanity is paying the costs for carbon emissions of the wealthy elite. Earth cannot afford Cornell’s ostentatious membership in the “polluter elite.” As an elite university, Cornell cannot escape the ethical dimensions of affluence that “overuse[s] the earth’s resources” and threatens life on earth.

To put carbon inequality in perspective: Cornell has a larger carbon footprint than the 22 lowest-emitting nations in the world (and larger than the bottom eight combined). Rather than challenging carbon inequality, Cornell promotes it through all the accouterments of affluence: hyperconsumption, frequent flying, personal car culture, constant campus growth, excessive square footage per person, wealth accumulation, discard culture, and massive waste production. This comes at a tremendous cost to local and international wellbeing.

If Cornell’s resource use and carbon pollution are a proxy for how they harvest, that harvest is maximizing rather than minimizing harm. Robin Wall Kimmerer points out that the inherent difficulty of certain harvesting activities is an important constraint: not everything should be convenient (p. 179). When it’s convenient, it becomes easy to take too much. Cornell’s culture, like that of the polluter elite generally, exalts carbon-intensive ways to free us from constraints, privileging convenience and speed in the pursuit of travel, study, endowment growth, and technocratic climate “solutions.” This all distracts us from the hard work of reducing consumption and redesigning our lives to live within earth’s means.

Cornell’s current Climate Action Plan preserves current levels of vast energy and material consumption while seeking “sustainable” fixes to meet or “offset” that demand. The pretense is that we can somehow maintain current levels of elite pollution while also meeting climate goals. We cannot. Cornell’s plan for “carbon neutrality” is a dangerous trap. The international consensus is clear and urgent: the globe’s “polluter elite” must rapidly and drastically cut their consumption in order to realize those emissions reductions. Cornell must begin actualizing the first step in their hierarchy of climate action: avoid carbon-intensive activities – and reorganize life at Cornell to do so.

When we consider the harm caused by Cornell’s carbon harvest, it becomes clear that continued inaction is the riskiest proposition on the table. Each additional year of business as usual at Cornell will emit at least 500,000 mtCO2 while foreclosing on critical windows of opportunity for climate advocacy, policy change, climate education, and community resilience. Given the estimate of one future excess death for every 1,000 tons of CO2 emitted, Cornell will be responsible for killing at least 500 future humans every year. That is an underestimate, because Cornell does not report its emissions from its investments or student travel. Cornellians, the community, and the planet cannot afford this inertia. This is by no means minimizing harm.

We “miscalculate the gap between where we are at and where we would like to be, and what we would need to relinquish to get there."

-Vanessa Machado de Oliveira, Hospicing Modernity

An adequate response to the climate emergency will uphold the Indigenous principle of unconditional accountability. We don’t mean philosophical, psychological, or legal ideas of moral accountability. We mean mortal accountability, the empirical, earth-bound, root-entangled accountability that exists between life forms in a shared ecosystem. The kind of accountability that says: if you pollute the air, everyone will breathe toxins. If you overharvest your relatives, their kind will die and you may too. If you ignore your relationships with other beings and reject your reciprocity with them, the lifeline that sustains you will be severed.

In short, this kind of accountability requires that institutions actually honor the pace and scale of change that science so clearly states is required. Problematically, this kind of accountability is lacking at Cornell.

First, Cornell is not even reporting the scope of the problem correctly. Their Baseline Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventory omits categories that account for the vast majority of their carbon footprint, reports only the Ithaca campus (ignoring other campuses), and underreports their emissions from methane gas, ignoring their own climate scientists’ advice and against NY State’s updated emissions reporting standards.

Furthermore, Cornell’s current Climate Action Plan is dangerously out of step with global climate goals. What we do between now and 2030 is critical. Global carbon emissions must be slashed at least 50% by 2030 to meet our climate goals and avoid locking in 2C warming and pushing climate tipping points. This requires that the globe’s richest 1%, including wealthy institutions like Cornell, take the lead in cutting their own outsized emissions by more than 50%. Cornell’s Climate Action Plan is inconsistent with this emissions-reduction pathway. Instead, Cornell plans to continue burning fracked methane gas until roughly 2035, at which point they hope to transition to more renewable heat with the ambitious Earth Source Heat project. This project faces unknown odds of success, public risks, and an ambiguous timeline for implementation. Meanwhile, Cornell has no plan to bring aviation and transport emissions to zero–nor do they report those emissions for students. As currently formulated, Cornell’s Climate Action Plan participates in a policy trajectory that “will be nothing short of cataclysmic” by locking us into 2C warming by 2030 and incurring a high risk of crossing climate tipping points.

Even if their Climate Action Plan were sufficient, Cornell is falling behind its own goals. Unbelievably, in the decade since Cornell’s 2013 Climate Action Plan promised continued steep GHG reductions, University emissions have actually increased year on year, with the exception of temporary reductions reflecting Covid-19 disrupted operations. Those jumped back up in 2023, the first full year post-Covid. Unbelievably, Fall 2023 saw the highest volume of staff and faculty flights on record. Cornell has not publicly reported the lag in their Climate Action Plan goals, nor has it updated its Climate Action Plan on the promised schedule.

Cornell’s failure to realize their own inadequate Climate Action Plan can be attributed to persistent failures to make brave tradeoffs in the name of climate. They are not holding themselves accountable. Instead of “reducing emissions that align with our mission,” as Cornell would have it, the university must rebuild their mission to preserve a habitable planet. A livable planet is not secondary to Cornell’s “mission-critical” activities. It is the basis for any activity at all.

We too are accountable within this system. Students, staff, and faculty can choose to stop being complicit in a destructive culture. We must demand policies from Cornell leadership that institutionalize comprehensive changes on an individual and systemic level: Travel less. Eliminate flying for educational exchanges. Support local and sustainable transportation. Pay the social cost of carbon on campus. Change your research protocol–permanently. Minimize greenhouses. Close the fume hoods. Request rolling blackouts when needed. Stop expanding campus. We need to start making brave tradeoffs in the name of climate – which means that we need to start holding ourselves accountable as the ones who are asking (and polluting) too much.

Since its founding, Cornell has benefited from the act of taking what was not given. The university stands upon traditional Gayogo̱hó:nǫɁ (Cayuga Nation) homelands obtained through coercive treaties. It was built from the proceeds of a land grab that continues to affect hundreds of Native communities, and its endowment still profits directly from Indigenous dispossession. This history of dispossession, broken treaties, and genocidal violence has yet to be officially acknowledged or redressed by Cornell University or the US government.

That legacy of entitlement and unaccountable taking continues in the University’s relationship to the contemporary local community. Cornell refuses or fights against paying its fair share to local municipalities, employees, or the school district, petitions to make itself exempt from local climate laws requiring fossil-fuel phaseout on new construction, and steamrolls fossil-fueled artificial turf projects against the local community’s and scientists’ well-founded health and environmental concerns.

As we survey Cornell’s carbon-intensive culture, we must recall that fossil fuels are “by no stretch of the imagination” given to us, but rather extracted and burned to “inflict irreparable damage” on earth (Braiding Sweetgrass, p. 187). Cornell’s business as usual is an act of taking what has never been given: methane gas is being taken from the Marcellus shale to feed its gas-fired power plant; the fossil fuel industry feeds its flows of donor money, research grants, and named buildings; while executives who profit from military and extractive industries fill the most powerful positions on Cornell’s Board of Trustees. And this is only scratching the surface.

When Cornell on Fire met with university leadership to argue for radical climate leadership, they told us that Cornell can’t take climate action because it needs to maintain its competitiveness, citing examples like constructing new business schools when their peer institutions do. Such pursuit of business as usual is driven by narrowly self-interested goals of prestige, power, and wealth, with no regard for the communities whose permission is implicated.

Cornell has not yet reduced their emissions, failing to abide by the answers suggested by their own acclaimed climate scientists and its own Climate Action Plan. If Cornell operates on the pretense of advancing scientific knowledge but fails to act in accord with that science, as is presently the case, the message is lost. As scholars point out in an article called “No Research on a Dead Planet,” “If those with privileged knowledge about the crisis carry on as usual it adds an insincerity to our warnings and communicates a lack of grounds for genuine concern…how then can we expect others to act?”

As an example, imagine being told by your professor that climate change and ecological collapse is accelerating to the point of large scale societal disruptions, unless radical action is taken now. Then, instead of doing anything remotely radical, the professor gives you a test and flies off to another conference, depositing several tons of greenhouse gas into your atmosphere to remain there for hundreds of years. Your university builds yet another new building and names it for a fossil fuel baron, while consolidating Trustee and donor leadership among fossil fuel and military profiteers. This “semblance of indifference” contributes to epidemic levels of climate anxiety among young people and condones societal inaction. It would be more accurate to refer to “climate honesty” instead of “climate anxiety”, and the position of those who refuse to take action “implicatory climate denial.”

As another example, the current tenure system actively discourages the ethic of abiding by, and speaking bravely about, the answers that earth is providing us. Earth’s feedback makes it clear that our societies have underestimated the challenges of avoiding a ghastly future, and “this dire situation places an extraordinary responsibility on scientists to speak out candidly and accurately when engaging with government, business, and the public.” Yet tenure review privileges peer-reviewed publications above activism, political action, public communication, outreach, and broader impact efforts. It is not enough to simply pour more money and carbon emissions into research. Tragically, “the compulsion to do ever more research on climate change” ignores the fact that the science is settled: we must cut emissions and consumption drastically and rapidly. Focusing exclusively on grants and publications as if the world were not in crisis is a disservice to humanity. And perversely, Cornell’s current narrowly-defined mission creates incentive structures that not only encourage, but actually pressure faculty to fly frequently.

Privileged people of all generations are complicit in the current carbon-intensive system, and those in positions of authority have a particular responsibility to lead the cultural change we need. Students are looking to faculty, “hungry for leadership that is brave enough to break from established norms and habits to usher in a world that will allow them to thrive.” Yet despite thousands of pages of peer-reviewed studies documenting the demise of our planet, institutions like Cornell are still failing to ask whether or not earth can provide for their continued business as usual.

“As producers and gatekeepers of knowledge, and as providers of education and training, our universities play a key role in the reproduction of unsustainability…[They need to] leverage their unique role as powerful anchor institutions to demonstrate climate justice innovations and catalyze social change toward a more equitable, renewable-based future.”

-Kinol et al., 2023. “Climate Justice in Higher Education.”

Cornell’s prestige and wealth create unique leverage points for change – and a unique responsibility for giving back in reciprocity for what was taken to build it. It can offer its gifts in the form of teaching and scholarship that are mobilized for the climate emergency, while serving as a living laboratory for how to do so in a way that is compatible with a livable planet.

Cornell has what it takes to meet the challenge of educating the next generation of climate leaders. But it is not yet doing so. Although climate change will redefine every student’s immediate future, not a single climate course is required. Cornell’s curriculum should teach to the interconnected climate and justice emergencies by prioritizing mitigation, adaptation, and resilience in every discipline. We know Cornell can do so because it has implemented mandatory “Writing in the Disciplines” for first-year students. Given the life-defining dimensions of the climate emergency, it should be given at least the same standing. Cornell’s curriculum must reflect a full-scale commitment to education for the climate crisis. Imagine “Climate Justice in the Disciplines,” which would include teaching core knowledge about the kind of energy transition that is worth fighting for in timescales that matter; how classic economic narratives have caused our crisis and how to change them; how individuals acting in concert create system change; how diverse knowledge systems and Indigenous principles can inform our response; and how to dial back lethally unsustainable levels of energy and material consumption. In short: the gift the world needs from Cornell is an education that questions the root causes of the climate crisis and prepares us to weather climate disruption while creating a more sustainable future.

Universities can catalyze societal transition through honesty, activism, and political engagement. Academics can fulfill their public role in the climate crisis through intensive science-society and science-industry action, collective action, and activated science for policy. As a basic condition, we need honesty. Academics must “explain honestly, clearly and without compromise, what scientific evidence tells us about the seriousness of the climate emergency.” Following that, we need academics’ behavior to accord with their words. Instead of sitting around in expansive offices and flying around to conferences documenting the demise of our planet, academics and their institutions must demand transformative change across all sectors and levels of their own University and society to meet the challenges of just mitigation and adaptation.

Universities can lead the way in the transition to zero-carbon. Cornell prides itself in its role as a “Living Laboratory for sustainability.” To do justice to that claim, it must lead the way by demonstrating an adequate full-scale response to the climate emergency. At a bare minimum, that would entail slashing emissions by 50% by 2030, and moving to zero rapidly afterward. Setting climate as the first priority will mean system-wide commitments to costly tradeoffs in the name of climate at all levels. Our current levels of grossly inequitable energy and material consumption must fall, steeply. This could entail ramping down operations, load-shedding, prioritizing plant-based diets, travel reductions, going virtual, becoming local, ceasing new construction, and seasonal operations.

By demonstrating the necessary transformation that broader society requires, Universities like Cornell can show the world what the climate emergency calls for. We know that Cornell can do so because they pivoted for Covid-19, and they can do so for climate breakdown. As Oxfam says, policy-makers’ response to Covid “showed they can be radical when there is no other choice.” And there is no non-radical future. We must now operationalize Cornell’s emissions reductions goals—and go beyond them—in the name of planetary survival. Cornell must redefine its operations and mission to meet our climate reality – not redefine our climate reality to meet its mission and operations.

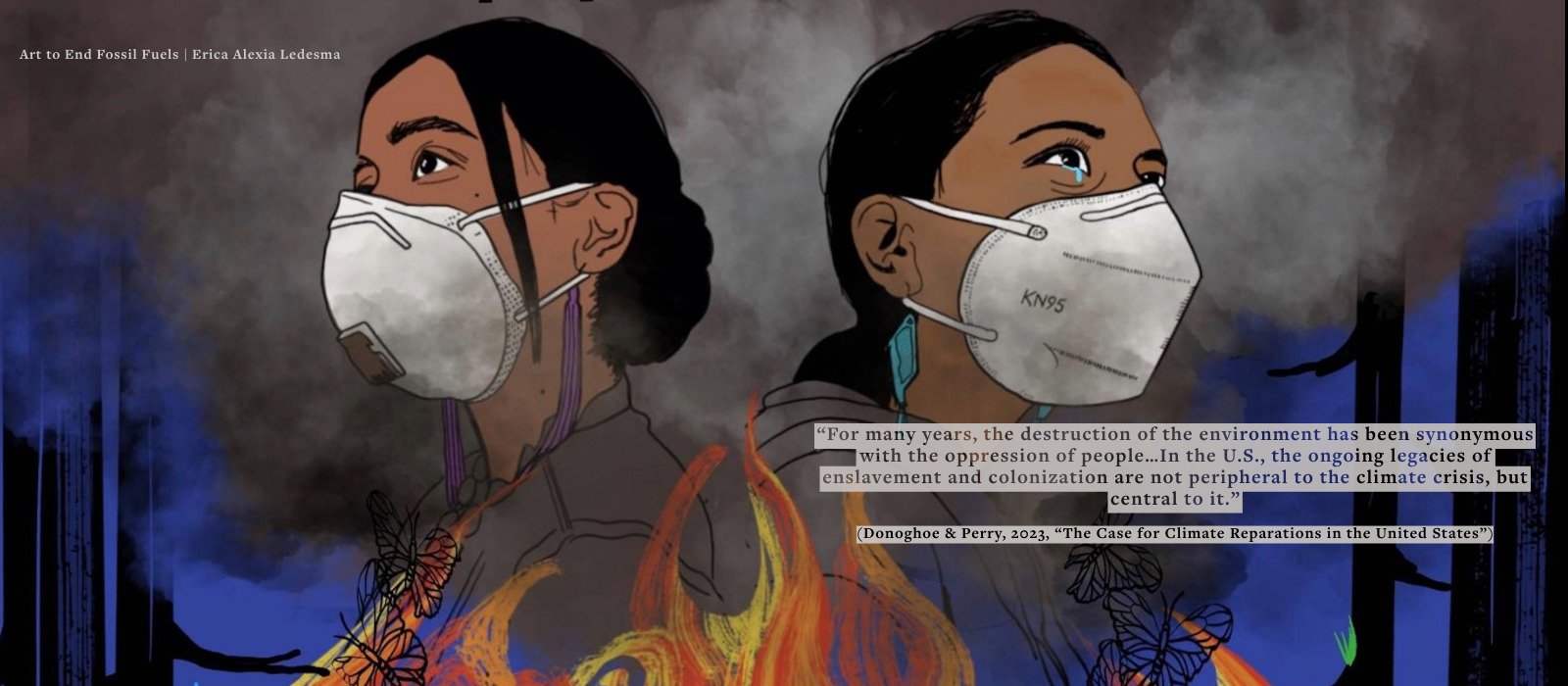

Sustaining life on earth requires system change, and system change requires leadership from climate justice communities. We will not solve the climate justice crisis with the same mindsets of extraction and exploitation that caused it. Elite institutions like Cornell must learn from BIPOC communities the skills of living in community, leading meaningful lives with less materialism, and relating to the land in a way that is restorative. Indigenous peoples have a singular role to play in restoring right relationship, by offering lifeways and knowledge systems that are proven to sustain biodiversity and respond adaptively to climate change. Cornell must follow their lead in addressing the root causes of the climate crisis while acknowledging that local knowledge has a critical role to play in the academy and climate policies. Climate justice and adequate climate action will also demand a reparative stance that foregrounds climate reparations and leadership from front-line communities.

It is time to restore right relationship with earth and one another. This Call to Action recognizes that it is hard to enact right relationship within dominant frameworks that implicitly or explicitly place humans outside “nature” and perpetuate many assumptions at the root of the climate crisis. The closest equivalent might be found in the concept of Scope X Emissions, referring to “work that restores and regenerates, that rebuilds the foundations of healthy ecosystems and thriving communities, that takes responsibility for system level emissions.” Scope X emissions go beyond Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions—which focus on reducing harm and “fixing symptoms”—by addressing root causes and taking responsibility for systems-wide change beyond one’s own institution. Cornell can move towards sustaining those who sustain it by taking full accountability for this form of systems-wide change.

Transformative action at Cornell will set a world-changing precedent. University campuses are a significant site for climate action, as seen in recent campus movements for climate emergency declarations, fossil fuel divestments, and fossil free research. Change can ripple quickly: after Bristol University declared a Climate Emergency in February 2019, hundreds of other universities quickly followed suit. Historically, universities have played a major role in social movements and have mobilized for public service in the face of emergencies such as war and pandemics.

Cornellians and community actors are poised to drive the inflection point. Our conversations with students, faculty, staff, and community members highlight widespread dissonance about continuing "academia as usual" in the face of an accelerating climate disaster, coupled with frustration at the lack of opportunities to engage in effective action. Cornell on Fire represents a collective means to break the silence and demand necessary changes now.

Cornell can make history by implementing a climate justice plan that is unprecedented in its scope and honesty. Invested with the will of its students, staff, and faculty, Cornell has the power to implement actions proportional to the scale of the crisis, guided by the work of thinkers and actors already present on these Gayogo̱hó:nǫɁ lands.

It will do so by recognizing that students deserve an academia that serves their future, that professors have a duty to speak truth to power, that multiple voices are needed including Indigenous ones, and that those with privilege, power, and resources have a duty to lead the way in system transition – including nonviolent direct action, if need be. This lays the foundation for a university that makes every decision in full awareness of and accountability to the climate emergency, based on the principles of an Honorable Harvest that will guide us to restorative right relationship.

“We should think about scale in terms of what our role is as ancestors. What world do we want to leave behind? And whatever practically we need to do to leave behind a good world, or at least the possibility of continuing the struggle for a good world is what we have to do.” (Olúfému Táíwò, (2022) “To Achieve Racial Justice we Must Rebuild the World—and Save the Planet”)

Cornell on Fire creates space for many voices to call on Cornell to confront the climate emergency and call for climate justice. Our demands uphold existing campaigns while catalyzing generative new changes for an educational system that is compatible with a livable planet.

We draw our name from the book Universities on Fire, which was published the same year we were formed (2023) by Bryan Alexander. Like its appellation, our movement is named for the following metaphorical resonances:

The world is on fire.

Hearts and minds are on fire.

Universities are sources of illumination.

We have a duty as torchbearers to lead the way.

System change requires collective action — a bucket brigade to save the world before it burns.

We must act in accord with the gravity of the climate emergency, because justice, earth, and our humanity demand it of us.

This Call to Action is a collective effort penned by the members of Cornell on Fire in November, 2024. It may change to meet the needs of our movement, community, and earth. We thank everyone who has contributed to our thinking in various ways through conversations, teachings, and review. Special thanks to our reviewers Michael Charles (Biological and Environmental Engineering and American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program at Cornell), Renata Leitao (Human Centered Design and American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program at Cornell), and Douglas Medin (Psychology Professor Emeritus at Northwestern). We also offer special gratitude to Robin Wall Kimmerer and all Indigenous scholars, activists, and community members who continue to offer much-needed teachings in action. We count ourselves among, and are grateful to, the community of people everywhere who are struggling for a livable planet. Cornell on Fire takes responsibility for any errors, and we invite feedback on all fronts.

“Time is no longer on our side. Let’s use what time we have more wisely.”

-Michael Mann and Tom Toles, (2018) The Madhouse Effect, p. 138