don’t muzzle us

Our response to the Cornell Committee on Expressive Activity Draft Report Policy

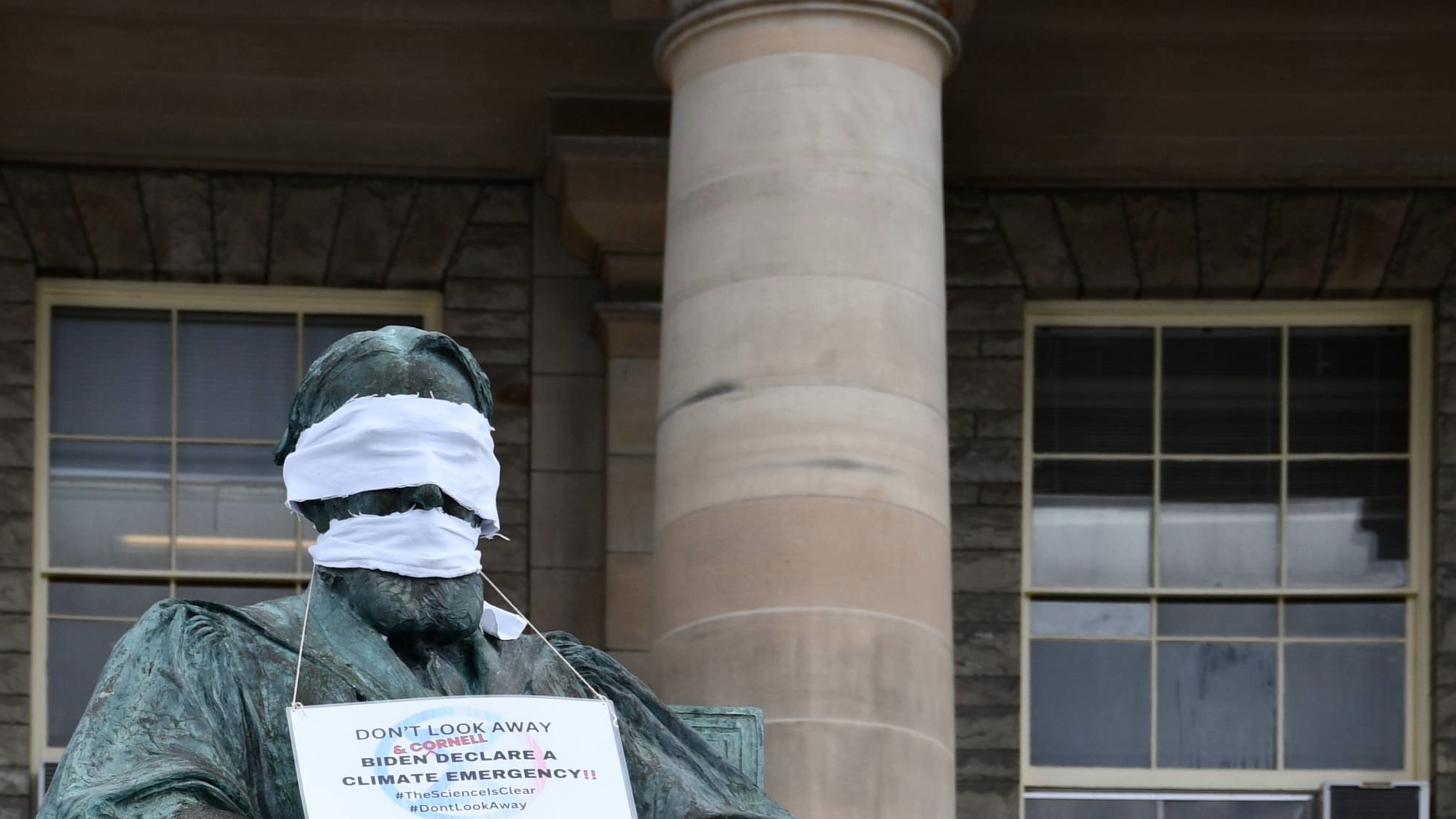

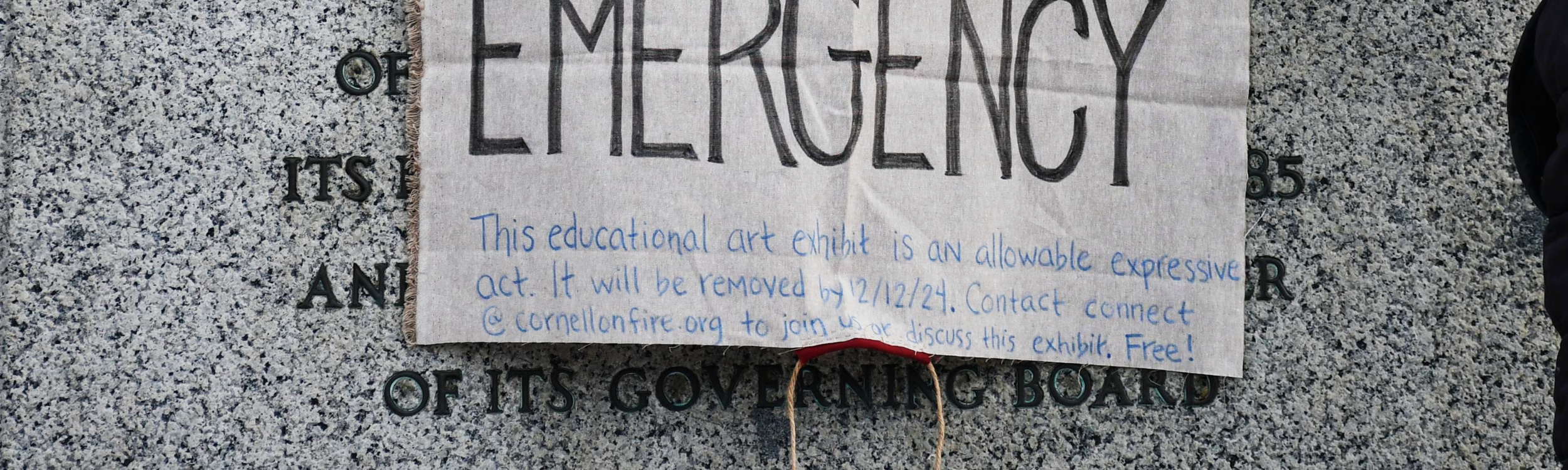

Delivered at the very moment(!) that AD White unexpectedly weighs in on the expressive policy

This statement is offered December 6, 2024, and may be revised.

Introduction

“In America the University has participated in the worst aspects of the society and only a few of the best—the worst including racism, class exclusion, and militarism.” [And ecocide.]

-Brian Eden and Paul Sawyer, quoting radical economist Doug Dowd in “Looking back at politics: Fifty years of activism at Cornell”

As members of the Cornell community working to advance Cornell’s response to climate justice through activism, including nonviolent direct action, we have closely reviewed the Cornell Committee on Expressive Activity (CCEA) draft report policy. We offer our response and comments below (all page numbers below refer to that document.)

We applaud the CCEA modifications of the interim expressive activity policy that (1) relax some restrictions on spontaneous gatherings, amplified sound, signs, and postering, as well as the requirement that only “recognized” groups be allowed to participate in such activities; and (2) call for a sweeping revision of the university’s rules and processes involving student suspension. We are also glad that the CCEA recognizes that “peaceful expressive activities including civil disobedience (e.g., sit ins)” should be allowed in certain settings if they do not displace others from shared spaces (p. 9).

However, we find that the draft policy does not adequately contend with either the historical evidence or contemporary reality of protest. First, the policy adheres to a vacuous definition of civil disobedience that prevents it from being disruptive in any way (see p. 10). Disrupting a harmful status quo is often the point of civil disobedience. History reveals that nonviolent disruptive protest has been essential to the movements that created the values Cornell upholds today: for instance, womens’ autonomy and equal rights, the establishment of the Cornell Africana Studies and Research Center, or divestment from South African apartheid. Those protests would be disallowed under the terms of this current document. Is it Cornell’s stance, then, that those disruptive protests should not have occurred? Furthermore, the draft policy’s emphasis on excessive policing and sterilization of protest (e.g., by pre-registration) are a distraction from the university’s actual responsibilities in the face of protest – to enter into conversation with the protestors and to consider their demands. History reveals that protesters have often had something of value to offer an administration wedded to a harmful status quo. The draft policy’s emphasis on policing and micromanaging protest must be dropped in order to make good on the authors’ own assertion that protest is “an indispensable part of the pursuit of knowledge” and also plays a key role in the university’s “civic mission” by “cultivating critical thinking skills and responsible citizenship” (p. 1). It is absurd to suggest that an indispensable pursuit of knowledge can only take place, for instance, between 12-1pm or after 5pm.

Further, our contemporary reality demands radical and transformative action if humanity is to survive. Therefore, if Cornell’s leadership is serious when they say that “Cornell’s students, staff, and faculty should be able to engage in their work and campus life without significant disruption,” then they must recognize and act to prevent the profound disruptions that will follow from climate breakdown (p. 2). This implies that Cornell’s expressive policy must recognize that the entire Cornell community–including its leadership–has a responsibility (not to mention a right) to speak out in protection of the institutional values it holds dear. There can be no “institutional neutrality” in the face of direct attacks on the university’s stated values, or the existential threat of climate breakdown. For that reason, we call on Cornell to Declare a Climate Emergency. Thousands of other universities have already taken this step: Cornell must do so, and deliver on their promise that Cornell is “uniquely positioned to operate on the speed, scale, and scope required to confront the climate emergency.”

Stepping back, it is valid to ask why the Cornell administration feels the need to revisit their expressive policy at all. As noted by the policy authors (p. 2), the administration’s current initiative to codify a new expressive policy occurs against the backdrop of war in the Middle East, and presumably in response to the repressive policies instigated last spring by Congress Republicans (led by Elise Stefanik). Arguably, free speech on campus should be left alone; after all, it is still under Constitutional protection. Our overall response to the idea of crafting a special policy on freedom of expression is to ask: what was inadequate about the previous policy and Constitutional provisions for free speech?

Finally, many of these principles will come down to who is enforcing the rules, as noted by the authors themselves (“Our committee recognizes that even the most thoughtfully written expressive activity policy is only as good as its implementation,” p. 14). This is a special concern at Cornell because of the university’s unwillingness and/or inability to confront fossil fuel elites and other special-interest elites in positions of power. It is also a special concern in our current political climate: the incoming US Presidential administration has made clear their intentions for free speech to be enforced in a biased and unaccountable manner. We have reason to ask whether those who are enforcing federal rules will be impartial. Here at Cornell, this has already begun to play out in coursework and the suppression of expression on campus. We must recognize the power imbalances at play among the university administration, such as the outsized role of capitalist elites affiliated with fossil fuels and the military among Cornell’s Board of Trustees. These individuals have a direct conflict of interest with Cornell’s institutional values for climate action and justice, and it is not unreasonable to be concerned that they will enforce these rules in a discriminatory manner. Therefore, although the report and policy frame their recommendations in terms of "content neutrality," the actual implementation may be anything but.

Below, we extend our commentary to address several point-by-point comments.

Point by point comments

[p.4] (from Principle 2): “Conduct and expression that prevent others from participating fully in the Cornell community, including harassment, intimidation, threats of violence, shutting down events, and defamation are unacceptable, inconsistent with our university values, potentially illegal, and amount to grave disrespect for the dignity of others.”

Response. These guidelines inappropriately restrict disruptive activity. It must be noted that the guidelines themselves are founded on values to which some actors and elements within our society are inherently opposed – disruptive expression may be necessary to protect those values in the face of such forces. If a self-identified fascist, white supremacist, or racist speaker is invited to campus, the community should be free to speak out in opposition, including nonviolent interference with the event. If a speaker who can be plausibly identified as a fascist is invited to campus by an extremist group (as it has often happened, under the “liberal” aegis of Kotlikoff, Malina, and their predecessors) the judgment about whether or not the event should be shut down or interfered with should be made by the campus community, without interference with their freedom of expression to make the case that the speaker fits the definition of fascist. The campus community should be free to contest events held by ecocidal and genocidal corporations. Calling out fascists and planet murderers by name is necessary and should be freely permitted.

[p.4] (from Principle 5): “Input from within the Cornell community can help support university leaders in balancing freedom of expression with other university values and objectives.”

Response. This puts the carriage before the horse. If Cornell is to be governed by the community itself – students, faculty, and staff (something that has never been the case, despite the “shared governance” red herring that we have been fed for decades), rather than by a self-selected group of super wealthy fossil fuel profiteers, financiers, and other corporate elites – then the university leadership should support the community in implementing their vision and not the other way around.

[p.5] (defining “Hostile Environment”): “Under well-established legal precedents, a hostile environment exists when a community member is subject to unwelcome conduct that a reasonable person would find to be objectively offensive and so severe or pervasive that it limits or denies the community member's ability to participate in or benefit from a university program or activity.”

Response.

(1) Legal precedents are beside the point here. In Germany under the NSDAP, as well as under the U.S. expansion to the West and the subsequent consolidation of its hegemony over the stolen lands, genocide was legal. Cornell’s reflexive acceptance of the authority of the U.S. legal system places it in the dubious company of past aiders and abetters of atrocities.

(2) There is an oxymoron in the suggested definition: a judgment by a person (reasonable or not) is necessarily subjective, which is why a person’s view can have no bearing on whether or not anything is “objectively offensive”. Should a person waving a swastika flag on the Arts Quad be deemed “reasonable”? Should we take into account what such people find offensive?

[p.6] (re Use of University space and Scheduling): “Our committee recommends that the use of the existing indoor and outdoor scheduling systems for other activities be used for expressive activity.”

Response. Requiring that a person pre-register their plan to stand with a banner next to a building’s entrance (without blocking it) or to sit on a lawn next to a sign is both funny and chilling. If adopted, it would be another step towards the militarization of policing, enclosures and theft of public spaces, and the demonization of peaceful protest. For instance, the presumption that registration is necessary to ensure “safety” presents an exaggerated view of protest’s potential harms and contributes to demonization. Universities must resist such trends rather than promoting them.

[p.6] (re Significant disruptive sound including amplified sound): “The committee views the interim expressive activity policy, which allows amplified sound in only two outdoor spaces on the Ithaca campus – Ho Plaza and the area in front of Day Hall, from 12 to 1pm – as overly narrow. In addition to these locations and times, we recommend considering the approach adopted by many of our peer academic institutions to allow significant disruptive sound, including amplified sound, for any activities (not just expressive activities) after 5pm on the Ithaca and Cornell Tech campuses, with the added requirement of avoiding disruption in proximity to evening class locations.”

Response. We find these regulations on sound to be still overly narrow, and indeed, to entail micromanaging of protest. The authors themselves assert that protest is “an indispensable part of the pursuit of knowledge” and also plays a key role in the university’s “civic mission” by “cultivating critical thinking skills and responsible citizenship” (p. 1). It is absurd to suggest that an indispensable pursuit of knowledge can only take place between 12-1pm or after 5pm. If protest and expressive freedom offer important benefits to the Cornell community, as the authors assert and as we concur, then they should be allowed to take place when and where their action is most likely to deliver the critical educational, awareness-raising, and policy-changing benefits intended. The protesters are in a position to make this decision on positive event impact; not the administration.

[p.10] (re Civil Disobedience): “We define civil disobedience as a knowing violation of the university’s time, place, and manner rules in a way that remains safe and nondisruptive, while expressing positions on matters of public concern. We encourage the university to be tolerant of such violations as much as possible while maintaining the safety and operations of the university and its constituents, ensuring that the activities of one group do not displace the activities of other groups.”

Response. As noted in our introduction, we object to defining civil disobedience so narrowly that it must remain nondisruptive at all times. Merriam Webster defines civil disobedience as a “refusal to obey governmental demands or commands especially as a nonviolent and usually collective means of forcing concessions from the government.” Nonviolent means of forcing concessions, by their nature, may involve disruption. Further, “encouraging” the university to do the right thing is akin to petitioning the Czar for clemency; the same goes for the qualification “as much as possible”. This approach to freedom of (nonviolent!) expression is objectionable in principle. Instead, the CCEA must demand that the university not interfere with such activities.

[p.10] (re Civil Disobedience): “We define civil disobedience as a knowing violation of the university’s time, place, and manner rules in a way that remains safe and nondisruptive, while expressing positions on matters of public concern. We encourage the university to be tolerant of such violations as much as possible while maintaining the safety and operations of the university and its constituents, ensuring that the activities of one group do not displace the activities of other groups.”

Response. As noted in our introduction, we object to defining civil disobedience so narrowly that it must remain nondisruptive at all times. Merriam Webster defines civil disobedience as a “refusal to obey governmental demands or commands especially as a nonviolent and usually collective means of forcing concessions from the government.” Nonviolent means of forcing concessions, by their nature, may involve disruption. Further, “encouraging” the university to do the right thing is akin to petitioning the Czar for clemency; the same goes for the qualification “as much as possible”. This approach to freedom of (nonviolent!) expression is objectionable in principle. Instead, the CCEA must demand that the university not interfere with such activities.

[p.10] (re Disruptions): “Disruption occurs when members of the Cornell community are inhibited in their ability to teach, conduct research, study, provide health care or other critical university services, or access or make use of university facilities. Disruption also occurs when the administrative or operational functions of the university are impeded.”

Response. As an example, consider a recruitment event featuring a fossil fuel company that is expanding its extractive operations, making false claims to the public, lobbying politicians to enable their activities, filling the Cornell Board of Trustees, and even funding research at Cornell. Imagine this is happening while the consensus of climate scientists (including those at Cornell) is that we must scale back fossil fuel use immediately or face consequences even worse than what is already unfolding across the earth. Now imagine the event is disrupted by students. Arguably, it is the recruiters in question who are being disruptive – of the planet’s ecosystem and everyone’s rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Consequently, the proposed definition of disruption is untenable.

Furthermore, imagine that prior to the recruitment event protest, the Student Assembly had passed a resolution to divest from these corporations, which the administration ignored, and then turned around to invite those very corporations to recruit on campus in direct contradiction of the SA resolution. One could argue that the student protesters had grounds for their disruption. More generally, this raises an important question for the current structure that concentrates unchecked decision-making power in the administration: when Assembly resolutions (from students, faculty, or others) are passed but ignored by the administration, what are appropriate next steps? Reason suggests that those next steps would include disruptive action or civil disobedience.

Thus, the definition of disruption must apply to everyone in the Cornell community, and it must consider that the protesters may be less disruptive than the actors whom they are protesting. For instance, Anne Meinig Smalling is an influential trustee. She inherited a fortune from her father’s work in fracked gas through the Williams Company and is now profiting from Igasamex, Mexico’s natural gas pipeline which has for years sought to “promot[e] the use of natural gas as an energy source” by advocating for “the “‘lifestyle’ of using natural gas over other energy sources.” Her family fortune drives mass climate disruption. Her work and that of the entire fossil fuel industry expands fossil fuels while ignoring and obfuscating their climate costs, triggering climate chaos that severely disrupts and inhibits the ability of Cornell’s community to do anything at all. The expressive policy must take these conditions into account and apply their analysis of disruption equally to those protested as well as those protesting. Note that this adds complexity to the concept of “content-neutral” rules.

Cornell must allow nonviolent disruptive action that is safe, peaceable, and limited in duration, with the explicit recognition that these actions often provide critical educational, awareness-raising, and policy-changing benefits for the Cornell community. We acknowledge that complete and permanent disruption is not to be tolerated, such as that perpetrated by some members of Cornell’s Board of Trustees, or by the establishment of Cornell through a land grab causing permanent disruption through Indigenous dispossession.

[p.15] (Expressive Activity Standing Committee): “We recommend a standing committee be formed comprised of [sic] faculty, staff, and students to serve as an ongoing resource to university leadership to support thoughtful decision making related to time, place, and manner violations related to expressive activity on campus. This committee should be well-versed in the literature around free expression on university campuses, it should take a One Cornell approach, and it should include shared governance representation.”

Response. To date, the phrase “shared governance” at Cornell has served as a fig leaf covering autocratic governance-by-diktat. With that in mind, we demand that the proposed Standing Committee not include any members of the administration who are vested with disciplinary power and are appointed by a top-down process (such as the provost, deans, and department chairs). The same goes for the “response team” proposed in point #4 on p.15: sending “monitors” to expressive events (as has happened on a number of recent occasions) may achieve the opposite of what a deescalation team is supposed to be about. The policy’s focus on policing distracts from the University’s actual responsibilities in the face of protest - to enter into conversation with the protestors and consider their demands.

[p.15] (re Human resources clarity for staff): “One theme that came up repeatedly in listening sessions involved the need for better communication with staff on whether and to what extent, academic freedom extended to staff and how professional conduct expectations mapped onto their expressive activity both inside and outside the work setting. We recommend additional clarity and information be given to staff at all levels to help understand their rights and responsibilities.”

Response. Instead of beating around the bush in the name of “clarity”, Cornell must immediately switch from “at will” to “just cause” mode of employment.

[p.16] (Re Institutional Neutrality): “During our listening sessions, the topic of institutional neutrality came up often. While Interim President Kotlikoff and Interim Provost Siliciano made a commitment to refrain from opining on national or global events that do not directly impact the university in their August 26, 2024, letter, it is not clear whether this will be a short- or longer-term approach at Cornell. The question of whether Cornell leadership should adopt an official position of institutional neutrality falls outside the scope of our committee's charge. However, our committee did think it would be sensible for the university to assemble a group to provide background analysis and possible recommendations.”

Response. It is indeed unconscionable that the university leadership treat climate change as not directly impacting the university (as Kotlikoff and Siliciano explicitly stated in their town hall with CAS). We strongly support the CCEA in their recommendation that this craven policy be scrutinized. At this stage, with the evidence on the subject contributed by the university’s own researchers, a policy of neutrality on climate change on the part of the university amounts to complicity in violence. Furthermore, it is wilful blindness to conclude from the available evidence that climate change is a distant problem that will not affect Cornell’s campus and the lives of its students, staff, faculty or indeed its financial assets.

Closing Words

While the current draft constitutes an improvement on the interim expressive activity policy, it is still lacking in many critical regards. To start fulfilling its long-standing claims to intellectual and educational leadership, Cornell must do much better. It can only become a true and respected leader by listening to members of its community, whose thoughts and aspirations must take precedence both over the administration’s knee-jerk authoritarian impulses and over the trustees’ financial interests and political motivations.

Our position on Cornell’s draft expressive action policy

We continue to condemn Cornell’s draft expressive action policy as currently formulated. It is a serious obstacle in the way of mass mobilization of our community for the most important challenge of our times. Its practices are especially vexing in view of the accelerating climate catastrophe. Given the scope of the crisis and the lack of national, state, and university leadership in this vital matter, only concerted action from below can make a difference during this crucial window for climate action.

The first step towards undoing its damage is for Cornell leadership to declare climate emergency — a key demand that Cornell on Fire has been voicing for the last year. In this critical window of time for climate action, with the university administration sleepwalking into disaster, none of us can afford to be silenced into inaction by threats of individual sanctions. The more of us realize this, the more powerful and persuasive a collective force for change we will become.

Signed,

Shimon Edelman | Cornell Professor, Psychology

bethany ojalehto mays | Cornell Alum, Former Assistant Professor | Mothers Out Front Tompkins

Élan Shapiro | Showing up for Racial Justice

Leila Wilmers | Regional Scholar, Einaudi Center for International Studies

Jacob Boes | Cornell Postdoctoral Associate

Margaret McCasland | Cornell Alum, Interfaith climate activist and community science educator

Todd Saddler | Extinction Rebellion Ithaca | Ithaca Catholic Worker

Peter McDonald, Dean and faculty emeritus, California State University, Fresno | Chair, Sustainable Finger Lakes (SFLX.org)

(for Cornell on Fire)